Ships of the desert

Ships of the desert

Ships of the desert

Ships of the desertThe 42-year-old Général Soumaré is the unlikely-looking flagship of the Compagnie Malienne de Navigation, Mali’s answer to Cunard. Thirty metres long, this floating three-storey edifice of beaten iron plates has been re-welded and re-rivetted so many times that I suspect not much of the original remains. But it floats and it works. Exactly on schedule, it slipped its moorings at Mopti and turned downstream towards the desert city of Gao. This was to be its last round trip of the season and its load was surprisingly light – a couple of hundred Malians travelling deck class, and a dozen or so foreigners in first and second class. I’d chosen second class, a good compromise as it turned out, with a bunk in a four-berth cabin and basic meals included in the fare.

Our first day was spent crossing the Niger’s famous ‘inland delta’, where the river fans out into several channels and lakes in a rich green plain teeming with birdlife. Some of the birds were undoubtedly European residents in Africa for the winter, like me. Then came a series of riverside villages, at each of which we moored for an hour or so. Villagers poured to the riverbank with animals both dead and alive to sell to the passengers, and the passengers in turn leapt ashore to set out their stalls of oranges, peppers, tomatoes and other produce not available in this part of Mali. Both sides also touted baskets of river fish – a definite case of compulsive shopping, I thought. The trading took place to frenzied shouting from the participants and hooting from the ship’s siren.

It may be that these unexpectedly successful stops delayed our progress, or perhaps the timetable had been drawn up by a hopeless fantasist, but for whatever reason the supposedly three-day journey took five. I didn’t mind. Watching the spectacular sunrises and sunsets, strolling through the impromptu markets and feeling the daily rhythm of activity on the river was an unforgettable privilege – if the ship had carried on to Niger and Nigeria I’d have happily gone with it.

As it was, its terminus was the sprawling, fly-blown city of Gao. I’m told that trans-Sahara travellers have been known to gape open-mouthed at Gao’s verdant main street and opulent emporia. All I can say is that coming from the other direction it feels like the end of the civilised world. I breakfasted in the semi-derelict Hotel Atlantîde, then set out through streets piled with putrid rubbish to search its sandy suburbs for the nearest recommended accommodation at the unpromisingly named Camping Bangu.

After a couple of days Gao did start to grow on me – especially the clamorous and friendly Grand Marché – but it was now New Year’s Eve and time to be off to Timbuktu. Taking a leaf from Robert Frost’s poem, I decided to follow the road less travelled, a desert piste along the north bank of the Niger. Four-wheel-drive pickups make the 250-mile journey three times a week, and as it happened one was leaving that afternoon. The trip would take eight hours, meaning if all went well I would be rolling into the legendary city about midnight.

Of course I didn’t expect for a moment that this would actually happen, but on the other hand neither was I prepared for how far things would go awry. I turned up at the appointed hour to find a throng gathered at the gates of the transport company, trying vainly to squeeze past a Mount Everest of sacks and assorted baggage. The pickup was just visible beyond. I felt an “It can’t be!” moment coming on. Sure enough, over the next hour the mountain was systematically piled onto the groaning pickup. Then, at a shout from the driver, 28 robed and turbanned Tuaregs leapt atop the swaying, bulging heap. I joined the scrum, and as we bounced out of town I settled into a square inch near the back.

My fellow-travellers were a jolly and spirited bunch, but as the hours passed the strain of clinging on began to take its toll and I could feel myself being inexorably squeezed over the side. With nightfall the temperature plummeted and my companions fell silent, elbowing for space and retreating into their swathed turbans till they were just ghostly shapes in the starlight. This was the first time I’d felt cold since arriving in Mali and it went deep into my bones. Late in the evening we stopped at a police post in the desert, and by the light of the policeman’s hurricane lamp I found to my amazement that the place was marked on my map. We were barely a third of the way to Timbuktu.

“How far is the river?” I asked the policeman. “Fifty metres,” he replied. “That settles it,” I shivered. “Timbuktu can wait till another day.” I watched until the pickup’s tail-lights disappeared round a dune, then put up my tent on the sandy riverbank and snuggled gratefully into the down sleeping bag. The Milky Way blazed down from an inky black sky, and its reflection in the water was bright enough to read my watch by. The time was just five minutes to midnight.

I awoke to a stunning New Year’s Day dawn over the Niger, and after warming myself in the sun’s rays packed the tent and trudged back to the police checkpoint. For the solitary incumbent Ibrahim Sogoba this was clearly a punishment posting. His sole job was to roll aside an oildrum whenever a vehicle turned up, which, if I understood him correctly, happened about once a day. We crouched over a miniature kettle sizzling on his brazier, and after a while shared the traditional desert pick-me-up of three tiny glasses of sweet tea. “The first is bitter, like death,” he grimaced. “The second is smooth, like life.” Then, grinning maniacally, he handed me the third. “This is almost pure sugar – like LOVE!”

Ibrahim was a lively companion for one ploughing such a lonely furrow. As the morning wore on, two men brought a sheep’s liver from a hut nearby, and he fried it up with the flair of a Jamie Oliver for the four of us to wolf down noisily. But towards midday another sound caught his attention. “Can you hear engines?” he asked. I couldn’t. We strained our ears. “I’m sure the big boat’s coming,” he insisted. We raced to the riverbank and sure enough there was the Général Soumaré half a mile away, chugging towards us in midstream. I stared entranced at its familiar shape. Then I turned back to the beach and spotted a tiny pirogue moored under a tree, and a thought flashed through my mind. “Do you know whose that is?” I asked Ibrahim. He pointed to the hut where the sheep’s liver had come from. I dashed over and hammered on the door, and within five minutes my breakfast companions were poling me towards the deep channel, one punting, the other bailing frantically, Ibrahim shouting encouragement from the bank. The Général Soumaré slowed to a crawl and I was hoisted on deck. To my surprise on this return journey it was practically empty of people, but the hold was crammed with sheep.

I was back on course! The crew joked about my unusual method of embarkation but I didn’t care a fig. Battling against the current was slow going, and I was to enjoy two more sunsets before the Général Soumaré finally docked at Kabara, the port for Timbuktu. The sheep objected noisily to the long voyage but for me it was paradise. But then I wasn’t stuffed in the hold.

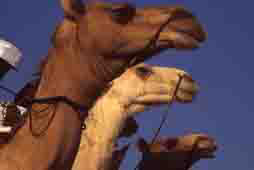

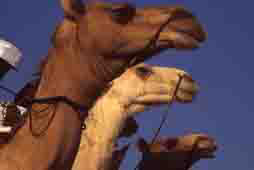

For nearly 900 years Timbuktu has left newcomers speechless. Its sand-blown alleyways seem permanently thronged with long-robed and turbanned Tuaregs, often just in from the desert with their flocks of sheep. Crumbling mud houses ring to the sound of greetings and banter, because this is a town where people enjoy gossip and engage in it constantly, the women over a cooking pot and the men over glasses of tea. Around them Timbuktu’s business proceeds as it always has. Donkey-carts piled high with sacks, cartons and baskets are tugged, heaved and cajoled round the open sewers and over the piles of sand that fill every street. Men of biblical appearance strike deals; children whoop and whistle in the dirt. In the two bazaars the noise reaches a crescendo as traders from the south join in the babel. Here, where there’s even less breathing space, upswellings of hot air carry pungent reminders of the produce of the desert, as greasy wool meets bloodied mutton meets dates, paprika and soap, occasionally rounded off with a teeth-grinding gust of sand.

Timbuktu was founded in the 12th Century, but became important in the 15th as a trans-shipment point for gold heading north from Djenné to Europe and salt heading south from Taoudenni to the markets of West Africa. Its position was perfect: right on the edge of the Sahara, but also just a few miles from the long-established trading route of the River Niger. Eventually traders were coming from all over North Africa and even from the Middle East, and in due course academics followed in their wake to study at the city’s university, which by the end of the 16th Century boasted 25,000 students – the largest in the world.

Timbuktu’s glory days are well and truly over, but incredibly some 30,000 manuscripts have survived from that time. Printed mostly in Arabic, they’re a priceless record of medieval Islamic scholarship. Some are in libraries but most are squirrelled away in private collections, the dry desert air turning them gradually to dust.

“Sand, salt and students,” I thought

as I gazed from the roof of the mud-brick room I’d taken

behind the kitchen at the Restaurant Poulet d’Or. I looked

forward to finding out more.